毗婆舍那实修教学

缅甸 沙达马然希禅师

(Saddhammaraṃsi Sayādaw)著

凯玛南荻法师 英译

温宗堃、何孟玲 中译

加拿大 佛陀教法中心 出版

(Buddha Sāsana Yeiktha)

公元 二○○八年 八月

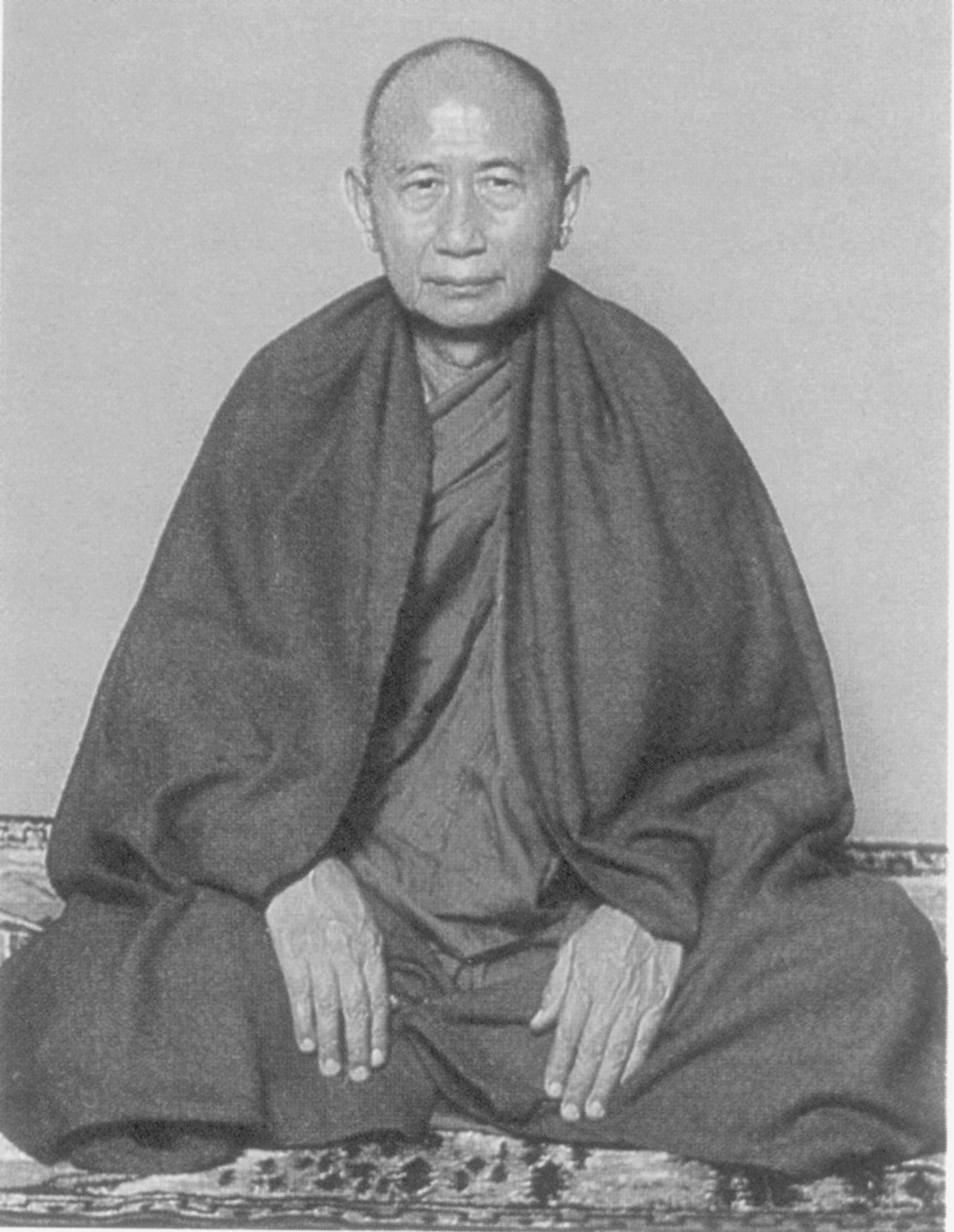

昆达拉毗旺沙禅师

(Sayādaw U Kuṇḍalābhivaṃsa)

目录

- 作者简介

- 英译者简介

- 毗婆舍那实修教学

- 作者序

- 壹.坐禅时的观照与标记

- 贰.行禅时的观照与标记

- 叁.一般活动的观照与标记

- 应谨记的座右铭

- 回向

- PRACTICAL / WORKING INSTRUCTIONS ON VIPASSANĀ MEDITATION

- INTRODUCTION

- Observing and Noting While in the Sitting Posture

- Observing and Noting While in the Walking Posture

- Observing and Noting on the General Details

- Maxims For Recollection

- Short Biography

作者简介

本书的原作者,是缅甸昆达拉毗旺沙禅师(Sayādaw U Kuṇḍalābhivaṃsa),又称为沙达马然希禅师 (Saddhammaraṃsi Sayādaw)。「昆达拉」(kuṇḍala)是禅师出家时的巴利法号,字义有「耳环」、「戒指」等环形宝饰之谓。巴利语「阿毗旺沙」(abhivaṃsa)的意思是「胜种」,这是年轻时通过高阶巴利语考试方能够获得的荣誉头衔。巴利语「沙达马然希」的意思,则是「正法光」或「妙法光」,这是禅师所创建、驻锡的禅修中心之名称。

昆达拉毗旺沙禅师是二十世纪内观禅修运动之父——马哈希尊者(Mahāsi Sayādaw, 1904–1982)的著名弟子之一,长久以来一直是仰光马哈希禅修中心总部的「导师」(Nāyaka)之一。生于一九二一年的禅师,九岁时出家,一九四O年受具足戒,曾于不同的著名寺院学习经教,在闻名的梅迪尼林寺教学长达二十年之久。禅师于一九五六年与一九五八年分别通过不同的巴利语考试,先后取得了两个「法阿阇黎」(Dhammācariya)的头衔。禅师于一九七七年跟随马哈希尊者修习毗婆舍那,于一九七八年被任命为禅修指导老师。一九七九年时,禅师在马哈希尊者的祝福下,于仰光市建立了沙达马然希禅修中心。之后,禅师分别于一九九三、一九九四及一九九五年创立了另外三个禅修中心。禅师的缅文著作相当丰富,代表作如《发趣论与毗婆舍那》(二册)。已被英译的著作则有《法的许愿树》(Dhamma Padetha)、《法的宝石》 (Dhamma Ratana),以及《强化内观行者诸根的九个要素》(The Nine Essential Factors which Strengthen the Indriya of A Vipassanā Meditating Yogi)。

中译本翻译自沙达马然希禅师原著,凯玛南荻(Daw Khemānandi)英译,加拿大「佛陀教法禅修中心」(Buddha Sāsana Yeiktha)于一九九九年出版、流通的Practical/Working Instructions on Vipassana Meditation。

英译者简介

本书的英译者是旅居加拿大的凯玛南荻法师(Sister Khemnānandi)。法师于一九三一年出生在缅甸传统的佛教家庭。一九五二年毕业于仰光大学,一九五五年获得美国宾州大学华顿学院的商业管理硕士学位。法师自一九六二年起便开始自己看书学习禅修,当时她是已有两个小孩的职业妇女。法师第一个正式的禅修老师是著名的韦布尊者(Ven. Webu Sayādaw, 1896–1977)。后来,韦布尊者去世,法师便改而跟随其他长老学习,直到在马哈希念处内观禅法中找到自己的归依处。

法师在一九八○年离开缅甸。在新加坡工作了八年后,于一九八八年移民加拿大。一九九四年时,法师在班迪达禅师(Paṇḍita Sayādaw)的勉励之下,供献出个人的住所,建立了「佛陀教法禅修中心」(The Buddha Sāsana Yeiktha)。一九九六年法师于美国加州「如来禅修中心」(TMC)在班迪达禅师引领下剃度出家,之后便一直担任「佛陀教法中心」的导师。一九九七年,法师到缅甸「沙达马然希禅修中心」接受沙达马然希禅师的指导,密集禅修一年。后来,她又跟随禅师至海外,参加了两次禅修营。在这之后,她又到沙达马然希禅师的禅修中心,进行了两次更密集的禅修训练。

毗婆舍那实修教学

作者序

在修习毗婆舍那〔即内观〕[1]的禅修者之中,尚未体证「法」(dhamma)[2]的禅修者,会希望迅速地获得体证;已体证「法」的禅修者,则会想在「法」上迅速地更进一步,希望能捷疾地亲证「圣法」(ariya dhamma)。如此,这些想迅速体证「法」、想在「法」上迅速获得进展,并快速亲证「圣法」的禅修者,必须先聆听「实修教学」,以便在修习毗婆舍那之时,能够完整地依循这些教导。禅修者必须能聆听、学习这些教导,如此方能达成「证法」的目的。

只是口头诵念,并不是毗婆舍那修行;仅凭借身体的精进,也不足以修习毗婆舍那。毗婆舍那修行,乃关乎我们的「心」。

因此,清楚明了下列几点,是极关紧要的事:

(1) 如何让心准确地直接落在禅修所缘上。

(2) 如何训练我们的心,不让它游移到外在的所缘。

(3) 如何以恰当的观照与标记,训练我们的心,使它能长时间保持不散乱的状态。

为了做到这些,禅修者应仔细阅读、学习、听闻且谨记这「实修教学」。因此,我建议所有希望有效率地修习毗婆舍那的人们,应好好地阅读、学习这「实修教学」。

沙达马然希禅师

Saddhammaraṃsi Sayādaw

毗婆舍那实修教学

(以下的内容,是沙达马然希禅师,对初到「沙达马然希禅修中心」学习毗婆舍那的禅修者,所做的毗婆舍那禅修入门开示。)

在修习毗婆舍那的禅修者之中,尚未体证「法」的禅修者,会希望迅速地获得体证;已体证「法」的禅修者,则会想在「法」上迅速地进步,希望能快速地亲证「圣法」。如此,为了快速地证「法」,也为了在「法」上快速进步,以便能快速地亲证「圣法」,你们应以最大的恭敬心与注意力,聆听下列关于「毗婆舍那修行」的开示。

综言之,此说明「修习毗婆舍那时应如何进行观照」的「实修教学」,共含三个部分:

(1) 坐禅时的观照与标记

(2) 行禅时的观照与标记

(3) 一般活动的观照与标记

壹.坐禅时的观照与标记

§ 1.1 观照腹部起伏

我将先说明坐禅时如何观照。要练习禅修之时,首先,你要找一个安静的地方,然后选择一个能让你坐得较久的舒适坐姿。你可以跪坐[7],或是盘腿坐。坐定之后,让背部与头部保持挺直,但不僵硬。接着,闭上眼睛,将注意力放在你的腹部。

当你吸气时,腹部会逐渐上升、膨胀。你必须贴近以紧密的注意力观察这腹部上升的过程,然后在心中标记「上」,并且,让你的心能够从腹部上升的开始一直到结束,都对准这上升的过程,而不游移到其它地方。

当你呼气时,腹部会逐渐下降、收缩。你必须贴近以紧密的注意力、精准地观察这腹部下降的过程,然后在心中标记「下」,并且让你的心,能够从下降的开始一直到结束,都对准这下降的过程,而不游移到其它地方。

§1.1.1 概念法与真实法

在观照、标记腹部的起伏时,你应该尽可能地不去注意腹部的形态、外形。当你吸气时,腹部内部会产生某种张力与推力,你必须密集地贴近观照并做标记,以便尽可能地感觉或觉知那发生在腹部内的「紧」(tension)与「推」(pushing)。腹部的形态、外形,仅是「概念法」(paññatti)。毗婆舍那修行,并不是为了了知「概念法」,而是为了了知「真实法」(paramattha)。发生于腹内的「推」(pushing)、「紧」(tension)、「压」(pressure)等等的现象,才是「真实法」。你必须贴近且准确地观照并做标记,如此才能够了知「真实法」。

当呼气时,你也应谨慎地观照并做标记。除了应尽可能地不去注意腹部的形态、外形之外,你还必须密集且准确地观照并做标记,尽可能地去了知那渐进、缓慢的「移动」、「振动」,及「收缩」的现象。[8]

§1.1.2 所缘的增减

如果你觉得,观照、标记「上、下」两个所缘,尚不能让心保持宁静,你可以再增加一个所缘,观照、标记:「上、下、触」。

在观照、标记「触」的时候,你应该尽可能地不去注意身体的形态、外形。你必须贴近且紧密地观照由于接触所产生的「硬」(hardness)与「紧」(tension)的现象,并予以标记。

如果仅依这三个所缘,你的心仍然无法专注,容易散乱,那么你可以再增加一个所缘,依四个所缘来观照、标记:「上、下、坐、触」。

当你观照并标记「坐」时,你必须将上半身视为一个整体,加以紧密地观照、标记,以便尽可能地了知身体「挺直」(stiffness)与「紧」(tension)的现象。你应尽量不去注意头、身体、手、脚的形态、外形。必须用心观照的,是那由于「风」的支持力所产生的「紧」(tension)与「压」(pressure)的现象,然后标记「坐」。这个「风」,则是由「想坐着」的动机所引发的。

当你以四个所缘做观照、标记「上、下、坐、触」时,你的心通常能够变得宁静。如果你发现观照、标记「上、下、坐、触」四个所缘,对你有帮助,那么你就可以继续如此观照下去。但是,如果发现这样观照、标记四个所缘,会让你的心变得紧绷、担心,以至无法好好地专注,那么你可以仅以三个所缘来观照、标记「上、下、触」。如果你发现依三个所缘所做的观照,仍然对你没有帮助,反而令你感到紧绷、担忧,那么,你可以仅观照、标记两个所缘[9]:「上、下」。主要的目的是,要让心平静下来,并培养出定力。

§1.1.3 观照妄想

作为初学者,在观照「上、下、坐、触」时,你的心可能会四处游移,譬如,想到佛塔、寺院、商店、住家等等。当你的心如此散乱时,你必须令观照心去观照那散乱的心,并标记:「分心」、「乱想」或「计划」等等。

当你的「定」(samādhi)与「智」(ñāṇa)变得更有力时,你会发现,在你观照、标记「分心」、「乱想」或「计划」等之时,散乱心便消逝不见。持续这样地观照、标记,你将能亲身体验到,散乱心在四、五个观照之后便消失不见。

其后,若你的「定」、「智」更为进步,并达至所谓的「坏灭智」(bhaṅgañāṇa)之时,在你观察、标记「分心」、「乱想」或「计划」的时候,你会发现那「想」或「计划」随着每一次的观照与标记而消逝不见。你会亲身体验到这些。

§1.1.4 洞见三共相

当你的「定」与「智」变得真正强而有力时,若你观照、标记「想」或「计划」,你不仅会见到这些「想」消失,也会见到那观照「想」的「能观之心」也消失。如此,你将了悟:不仅念头、妄想、计划的心不是恒常的,就连能观照的心也不是恒常的,它们全都是「无常的」(anicca)。

禅修者也会了悟到,如此一连串快速而急促的生、灭[10],像是一种折磨,或者说是「苦」(dukkha)。如何才能免除这些如折磨般的苦、不断生灭的苦呢?完全没有办法免除这种苦。这种生、灭与苦,有其自己的规律。它们不受控制,是「无我的」(anatta)。如此,禅修者便了悟、洞察到「无常」(anica)、「苦」(dukkha)、「无我」(anatta)的真理。

§ 1.2 三种观痛的方式

就初学者而言,持续观照、标记「上、下、坐、触」,大约半小时或四十五分钟之后,你将发现你的四肢开始隐隐作痛,或感到刺痛等不舒服的感觉。当这类感觉生起时,你必须将观照的所缘改为这些疼痛的「苦受」(dukkha vedanā)。

对于这类的疼痛、苦受,有三种观察的方式:

(1)第一种是,为了让疼痛消失,才观察疼痛。

(2)第二种是,带着与疼痛决战的敌对心态,下定决心观察疼痛,想要在这一坐之中或这一天之内彻底去除疼痛。

(3)第三种是,纯粹为了洞察疼痛的真实本质而观察疼痛。

第一种想要让疼痛消失而观察疼痛的方式,表示禅修者实际上贪着无疼痛的快乐,意味着禅修者当下对乐受有所贪爱(lobha)。禅修本是为了去除我们的「贪」,但是现在禅修者的观照却夹杂着「贪」。由于这个「贪」,禅修者将要花很长的时间方能体证「法」,方能在「法」上更加进步。[11]这就是为什么禅修者不应该以第一种方式来观照的原因。

在第二种方式,禅修者带着与疼痛决战的敌对态度,下定决心要在一坐之中或一天之内彻底去除疼痛。这敌对的态度,表示其中带有「瞋」(dosa)心所与「忧」(domanassa)心所。换句话说,这决心夹杂着「瞋」与「忧」,而这意味着,他的观照其实也有瞋与忧间杂其中。因为如此,禅修者得要花很长的时间才能体证「法」,才能在「法」上更加进步。这就是为什么禅修者也不应该以第二种方式进行观照的原因。

在第三种方式,观察疼痛只是为了要了知疼痛的真实本质。这才是正确的观照方式。禅修者唯有在了知疼痛的真实本质之后,他才能见到疼痛的生(udaya)、灭(vaya)。

§ 1.2.1 观痛的技巧与过程

禅修者观察疼痛时,必须要能了知疼痛的本质。当疼痛出现时,禅修者的身、心通常容易随着疼痛的增强而变得紧绷。但是,他应该试着不让自己变得这样绷紧,应该试着让身、心放松。禅修者也容易变得担心:「是否这一整支香或一整个小时,都得忍受这个痛!」无论如何,禅修者应小心避免有这样的担忧。

你应该让自己保持平静,抱持如此的态度:「疼痛随它自己的意向来、去;我的责任只是对疼痛保持观照」。你也应该抱持「我应忍耐疼痛」的态度。面对疼痛时,最重要的,就是学习忍耐。(缅甸的)谚语:「忍耐导致涅盘」,是修念处禅修时最有用的格言。

决定自己将忍耐之后,应注意让心保持宁静、放松,别让[12]身、心变得紧绷。保持身、心放松。然后,你必须将心直接对准疼痛。

接着,你应试着贴近且密集地观照疼痛,以便了知疼痛的强度与范围——它有多痛?哪个地方的痛最剧烈——是在皮肤、肌肉、骨头或是骨髓?如此贴近且密集地观照之后,你才视疼痛的类型来作标记:「痛」、「刺痛」等等。

接下来的观照,也必须紧密而准确地观照着疼痛的范围与强度,并依情况为每个疼痛做适当的标记。对疼痛的观照与标记,必须精确、有穿透力,绝不能仅止于肤浅地观照、只是机械化地快速标记「痛、痛」、「刺痛、刺痛」。你的观照与标记,必须准确而密集。当你如此准确而密集地观照时,你将清楚地体验到,在四或五个观照与标记之后,原本的疼痛会变得愈加剧烈。

当痛达至极点时,它会自行减弱、缓和,此时,你不应放松你的观照与标记,相反地,你应该持续热忱、认真地观照每一种疼痛。之后,你将会亲身体验到,每一种痛在四或五个观照与标记后,变得愈来愈微弱。某类的痛会变得愈来愈弱,另一类的痛也变弱;有的痛,则会转移到其它地方。

当禅修者如此观见痛的变化性质之时,他会对观痛的练习,愈来愈感兴趣。〔总之,〕持续精勤修行,当「定」(samādhi)与「智」(ñāṇa)变得更锐利而强大时,禅修者将体验到疼痛随着每次的观照而变得更强烈。[13]

当痛达其顶点后,它通常会自行减弱。这时候,禅修者不应放松他的观照与标记的强度,他必须以同样的精进与准确度持续地观照。然后,禅修者将亲身体验:痛会随着每次的观照而减弱;痛会改变位置,在其它地方出现。如此,禅修者会了悟到,痛也不是恒常的,它一直在变化,它会变强也会变弱。如此,禅修者便对疼痛的本质有了更多的了悟。

§1.2.2 观痛与坏灭智

这样地持续观照,当定与智变得更强有力,而达到「坏灭智」(bhaṅgañāṇa)的观智阶段时,禅修者会像是以肉眼亲见一样,清楚体验到,疼痛随着每一次的观照而完全地止灭,就像是骤然被拔除掉一般。

如此,当禅修者见到痛随着每次的观照而消失时,他了悟到:疼痛是无常的!现在,观察的心已能战胜疼痛。

随着定与智更加深化,「坏灭智」锐利的人们,能够在每一次观照时了知到,不仅疼痛灭去,连能观的心也随之而灭去。

若是观智特别锐利的禅修者,他们会清楚地看见三阶段的灭去,也就是,当他观照且标记「痛」的时候,「痛」先灭去,然后「觉知痛的心」灭去,接着「观照疼痛的心」也灭去。[14]禅修者会亲自体验这些。

§1.2.3 观痛时见三共相

如此,禅修者在心中自然地了悟到,痛不是恒常不变的,感受痛的心也不是,观照痛的心也不是。这就是「无常」(anicca)。一连串的快速坏灭,像是一种折磨,也就是「苦」(dukkha)。这坏灭的现象,不受任何人控制,也无法避免,它有其自己的规律,即是「无我」(anatta)。如此,禅修者以智慧亲身了悟到「无常」等的真理。

当禅修者依其自心了悟到,「痛」是「无常的」、「苦的」、「无我的」(不受控制)之时,在他对无常、苦、无我的洞察,达到明晰、彻底且决定的时候,他将能证悟向来所期待的「圣法」。关于如何观察、标记「苦受」,以上的说明,已相当完整了。

§ 1.3 闻声时的观照与标记

在练习时,你可能会听到外面的声音,也可能会见到或嗅到什么。尤其是,你也许会听到诸如鸡、小鸟的叫声、敲敲打打的声音、人车的声音等等。当你听到这些声音时,你必须观照它们并标记:「听到、听到」。你应试着这么做,以便能够做到只是纯粹听到,也就是,你必须试着不让心跟随那些声音,不让心被对声音的想象给带走。你应注意,让听到只是纯粹的听到,观察并标记「听到、听到」。[15]

当定与智变得强而有力时,若你观照并标记:「听到、听到」,那声音会变得不清晰,像是从远处传来似的,或像被带到远方,或像愈来愈接近、或变得沙哑不清楚。如果你有这些经验,那表示你已有能力观照能听的心。

以这个方式继续观照、标记,当你的定与智变得更强而有力时,你会发现,在观照、标记「听到、听到」之际,声音一个音节一个音节地消逝、灭去;能听(声音)的心识,也一个一个灭去;观照、标记的心也同样地灭去。观智锐利的禅修者,能够明确、清楚地体验这些现象。

在观照、标记声音时,尤为明显的是,声音一个音节一个音节地灭去,即使是初学者也可能会有这个体验。这些声音彼此不再相连结,它们一个音节一个音节地灭去。例如,当禅修者听到「先生」这个声音,观照并标记「听到、听到」,他会体验到「先」这个音节先个别地灭去,「生」这个音节随后也个别地灭去。如此,这些声音断断续续地被听到,以至于声音所表达的意思变得模糊不清、难以理解。此时,变得显著的,只是断断续续的声音之坏灭。

当你体验到声音的灭去,你将了悟到声音不是恒常的;当你体验到观照与标记的心也灭去时,你将了悟到能观照、标记的心也不是恒常的。如此,你将了悟,听到的声音与能观照的心都不是恒常的。这即是「无常」(anicca)。[16]一连串迅速灭去的现象,则像是一种折磨,是苦(dukkha)。

如何能免除这些折磨、苦呢?没有办法可以停止或免除它们。这坏灭之苦有其自己的规律,它是不受控制的,是「无我的」。如此,在观照、标记「听到、听到」时,禅修者将能洞察无常、苦、无我的真理,并且证悟圣法。

§ 1.4 坐时观照,即修四念处

在坐禅时,观照、标记「上」、「下」、「坐」、「触」,这和「身」(kāya)有关,所以被说为是「身随观念处」。观照、标记「痛」、「麻」、「痒」,则和「受」(vedanā)有关,所以被称为「受随观念处」。观照、标记种种念头「分心」、「计划」、「想」等,和「心」(citta)有关,所以被称作「心随观念处」。观照、标记「看到」、「听到」、「闻到」等,则和总称为「法」(dhamma)的身、心现象有关,所以被称为「法随观念处」。

如此,依据我们的恩师马哈希尊者所教导的方式练习坐禅之时,其中便已包括了身、受、心、法四个念处的修习。关于坐禅,以上的说明,已相当完整了。

贰.行禅时的观照与标记

接着,要说明行禅时如何观照、标记。行禅时的观照、标记方式,可分为四种:[17]

(1) 观照时,一步做一个标记。

(2) 观照时,一步做两个标记。

(3) 观照时,一步做三个标记。

(4) 观照时,一步做六个标记。

§ 2.1 观照时,一步做一个标记

第一种方式,禅修者观照时,将〔左或右脚的〕步伐看成一个移动,标记作「左脚」或「右脚」。

当你观照、标记「左脚」时,你必须贴近且密集地观照,以便能够了知,从脚步的开始到结束,整个逐渐向前移动的现象。你应试着尽可能地不去注意脚板的形态、外形。观照右脚的方式,也是如此。你必须贴近且密集地观照,以便能够了知从脚步的开始到结束,整个逐渐向前移动的现象之本质。你应试着尽可能地不去注意脚板的形态、外形。关于一步做一个标记,以上的说明,已相当完整了。

§ 2.2 观照时,一步做两个标记

以第二种方式观照时,将一个步伐标记为两个移动:「提起、放下」。当你观照、标记「提起」之时,你必须尽可能地专注于那一点一点逐渐上移的移动现象。你应试着尽可能地不去注意脚板的形态、外形。同样地,当你观照「放下」时,你应试着尽可能地不去注意脚板的形态、外形,只是一心一意地密集地观照那一点一点逐渐下降的移动现象。[18]

脚板的形态、外形是「概念法」(paññatti),概念法并不是毗婆舍那所要观照的所缘。「推动」、「移动」的现象,则是「真实法」(paramattha),为「风大」(vāyo)。关于一步做两个标记,以上的说明,已相当完整了。

§ 2.3 观照时,一步做三个标记

第三种方式,观照时将一个步伐标记为三个移动:「提起、推出、放下」。当你观照、标记「提起」之时,你必须尽可能地贴近且密集地观照并标记,以便了知那逐渐上移的移动现象。当你观照、标记「推出」时,你必须尽可能地贴近且密集地观照并标记,以便了知那逐渐向前的移动现象。同样地,当你观照「放下」时,你也必须尽可能地贴近且密集地观照并标记,以便了知那逐渐向下的移动现象。

如此贴近且密集地观照、标记时,你的观照与标记应保持在「(相续)当下」(santati paccuppanna)的「移动」上。你必须贴近且密集地观照,以便了知那移动现象的本质,亦即「真实法」(paramattha)。若你能够这样贴近且密集地观照,在你观照、标记「提起」时,你不仅会亲身经验到提起时一点一点逐渐上升的移动,也会经验到脚在上移时,变得愈来愈轻盈。

当你如此观照、标记「推出」时,你不仅会经验到推出时逐渐前移的移动,也会经验到脚在前移时变得轻快。[19]同样的,当你如此观照、标记「放下」时,你不仅会经验到放脚时一点一点逐渐下移的移动,也会经验到脚在下降时变得愈来愈沉重。

禅修者在观照、标记「提起」时,经验到〔脚〕逐渐上提时的轻盈感;观照、标记「推出」时,经验到〔脚〕逐渐前移时的轻盈感;观照、标记「放下」时,经验到〔脚〕逐渐下移时的沉重感。这时,他会对自己的练习更加感到兴趣。这表示禅修者已开始体证「法」了。

经验不同移动〔即提起、推出之时〕的「轻盈感」,表示体验到了「火界」(tejo dhātu)的特性—冷、热的性质,以及与「风界」 (vāyo dhātu)的特性—移动的性质。经验到〔脚〕下降移动的「沉重感」,表示体验到「地界」 (pathavī dhātu)的特性—粗、硬的性质,以及「水界」(āpodhātu)的特性—流动、凝结的性质。经验这些现象时,表示禅修者开始体验「法」了。关于一步做三个标记,以上的说明,已相当完整。

§ 2.4 观照时,一步做六个标记

第四种方式是,观照时将一个步伐标记为六个移动:「提起开始、提起结束、推出开始、推出结束、放下开始、放下结束」。「提起开始」指唯有脚后跟被提起而已,「提起结束」指脚趾也已提起。「推出开始」指脚板开始推出。「推出结束」指脚板在下降之前的短暂静止阶段。「放下开始」指〔脚〕开始下降的阶段。「放下结束」指脚板接触到地面的时候。实际上,这只是把一步里的三个移动[20],个别标记出其「开始」与「结束」而已。

另一种方式,是观照时标记「想要提起、提起、想要推出、推出、想要放下、放下」。在这种标记的方式里,禅修者分别观照、标记了「名」(nāma),即「想要…」的动机,以及「色」(rūpa),如脚板的提起等等。

还有另一种方式是,观照时标记「提起、抬起、推出、放下、接触、压下」。当你观照、标记「提起」时,是仅仅后脚跟开始提起的阶段。「抬起」指整个脚板连同脚趾被抬起。「推出」指把脚板推出的整个动作。「放下」指开始要把脚往下放。「接触」指脚板刚接触到地面。「压下」指将脚下压以便提起另一只脚。如此,你将标记六个移动「提起、抬起、推出、放下、接触、压下」。

许多禅修者藉由标记如上所述的六个移动,而培养出「定」(samādhi)与「智」(ñāṇa),他们的观照因而能得以进步,并能以非凡的方式体证「法」。关于一步做六个标记,以上的说明,已相当完整了。

叁.一般活动的观照与标记

「一般活动的观照」,指在坐禅、行禅的时间之外所做的观照。一般活动,包含你返回住所时所做的种种不起眼的动作,如开门、关门、整理床铺、换衣服、洗衣服、准备食物、用餐、喝水等等。这些动作也都要加以观照、标记。[21]

§ 3.1 用餐时的观照与标记

看到食物时,你必须观照、标记「看到、看到」。当你伸手拿食物时,要观照、标记「伸出、伸出」。当你碰触到食物时,观照、标记「接触、接触」。当你收集、整理食物时,观照、标记「整理、整理」。当你把食物取回到嘴边时,你要观照、标记「取回、取回」。当你低下头要用食时,要观照、标记「弯下、弯下」。当你张开嘴巴时,要观照、标记「张开、张开」。当你把食物放到嘴里时,要观照、标记「放、放」。当你再次抬起头时,要观照、标记「抬、抬」。当你咀嚼食物时,要观照、标记「咀嚼、咀嚼」。当你觉察味道的时候,要观照、标记「知道、知道」。当你吞咽食物时,要观照、标记「吞、吞」。

以上的教导,符合我们的恩师马哈希尊者所教导的在进餐时所做的观照方式。这些教导,是针对那些重视自己的修行,且恭敬、密集而毫无间断地持续修行的禅修者而说的。

在修习之初,你可能无法观照、标记到所有的动作,乃至会忘记去观照大部分的动作,但是不必因此感到灰心气馁。以后,当你的定与智变得成熟时,你将能够观照、标记所有的动作。

在修习之初,你应先试着专注那些对你而言最为显著的动作,将它当作主要的所缘。什么是对你而言最为显著的动作?譬如,若伸手的动作最显著可知,你就应该试着去观照、标记「伸出、伸出」,而无任何的遗漏与忘失;如果低头的动作最显著,那就应观照、标记「低头、低头」,而无任何的遗漏与忘失;[22]如果咀嚼是最显著的动作,那就应观照、标记「咀嚼、咀嚼」,而无任何的遗漏与忘失。如此,你必须观照、标记至少一个显著的动作,将之当作主要的所缘,而无任何的遗漏与忘失。

一旦你可以如此让心紧密且准确地专注在一个所缘,并藉此培养出定力时,你将能专注观照其它的动作,并培养出更深的定与智。种种的毗婆舍那智慧将因此而展开,而禅修者甚至能在进餐时证悟圣法。

用餐时,咀嚼的动作是尤为显著的。我们的恩师马哈希尊者曾经说过,在咀嚼时,上、下颚之中,仅下颚在移动。这下颚的移动,实际上就是我们所说的「嚼」。

如果你对下颚逐渐移动的过程,观照、标记得好,并培养出定力,你将会发现对咀嚼动作的观照、标记会进行得特别地好。从咀嚼的动作开始,接着你将能够观照、标记进食中所有的动作。关于如何观照进餐时的一般活动,以上的说明,已相当完整了。

§ 3.2 观照、标记坐下的过程

应观照的一般活动,也包含「坐」、「站」、「屈」、「伸」等动作。对具备了某程度的定与智的禅修者而言,当他正要坐下时,「想要坐下的动机」会相当显著。因此,禅修者必须观照这个「动机」、「意欲」,[23]标记「想坐下、想坐下」。然后,当坐下的动作进行时,必须观照、标记「坐下、坐下」。

当你观照、标记「坐下」时,试着尽可能地不要去注意头、身体、脚等等的形状。你应尽可能地贴近且密集地观照、标记那逐渐一点一点下降的移动现象,如此观照能使你的心精确地落在当下逐渐下移的动作。

你应非常贴近且密集地观照,以便能够了知移动的真实性质(paramattha真实法)。当你观照、标记「坐下、坐下」时,若你能贴近且紧密地观照、标记,且让你的观照心准确地落在「相续现在」〔即,当下〕的移动时,你将清楚地知道,身体下移时,你不仅觉知那逐渐下降的移动,也将感受到身体变得愈来愈沉重。

§ 3.3 观照、标记起身的过程

当你要结束坐禅,打算起身站起来的时候,若你很有正念,「想要起身」的动机会先变得显著。你必须观照、标记这个动机:「想要起身、想要起身」。这想要起身的动机,会使推动身体的「风界」(vāyo dhātu)开始运转。在你向前屈身,累积力气要起身之际,你必须观照、标记「使力、使力」。接着,当你将手伸向旁边做为支撑时,你必须观照、标记「支撑、支撑」。

当身体充满力气时,它会逐渐地向上升。[24]这个上升的动作,在缅语的词汇里称为「起身」或「起立」。我们观照、标记它作「起身、起身」。不过,语词也仅是「概念法」(paññatti)。我们要清楚了知的,是一点一点逐渐上升的移动现象。同样的,我们必须密集且准确地观照,并做标记,以便让心能够保持在「当下」逐渐上升的动作。

当你如此贴近、密集且准确地观照,而能让心保持在「当下」,并了知「真实法」之时,在观照、标记「起身、起身」之际,当身体上升时,除了了知逐渐上升的移动之外,你也将亲身体验到上升时的轻盈感觉。

如此,当你观照、标记「坐下、坐下」时,你将亲自体验到沉重的感觉与逐渐下降的移动;当你观照、标记「起身、起身」时,你将亲自体验到轻盈的感觉与逐渐上升的移动。如此,体验到〔身体〕上升时的轻盈感觉,表示你观见「火界」与「风界」的特质;体验到〔身体〕下降时的沉重感觉,表示你观见「地界」与「水界」的特质。

§ 3.4 见生灭

箴言:「见自相已,方见生灭。」

了知某一〔移动〕现象的特质之后,才会了知所谓的生(udaya)、灭(vaya),亦即,[25]观见每个移动剎那剎那地生起又灭去。一个移动生起、灭去,接着,另一个移动也生起、灭去,然后另一个移动又生起、灭去,如此生灭不断。清楚地见到生与灭,即是见到「有为相」(saṅkhata-lakkhaṇa)(一切身、心现象皆具有这「依缘而起」或「合会而成」的性质)。

如此见生灭之后,持续不懈地观照、标记,定与智会变得更强而有力。接着,你将发现「生起」的现象不再那么明显,只有「灭去」的现象是显著的。当更清楚地体验「灭」的现象时,禅修者会了悟到,身体的移动无一是恒常的。当禅修者清楚地看见观照的心也灭去,他将了悟到能观的心也不是恒常的,无论是「名法」(nāma)或「色法」(rūpa)皆是「无常的」(anicca)。

一连串快速的灭去现象,像是一种「折磨」、「苦」(dukkha)。我们无法阻止、避免这灭去的现象与苦,它们自行发生,不受任何人控制,是「无我的」(anatta)。当了知无常、苦、无我的观智,发展至非常明晰、彻底且具决定性时,禅修者将能证得一直以来所希求的圣法。

如此,在观照、标记「坐下」、「起身」时,禅修者将了悟到三种名为「共相」(sāmañña-lakkhaṇa)的共同性质:「无常」、「苦」及「无我」。当禅修者对三共相的了知,变得明晰、彻底且具决定性时,他将能证得一直以来所希求的圣法。[26]

§ 3.5 观照、标记弯曲与伸直

一般活动的观照,也包含对肢体的弯曲与伸直的观照。当你弯曲手臂时,若你很有正念,「想要弯曲」的动机会先变得显著。就此,你必须观照、标记「想弯曲、想弯曲」。之后,你应尽可能地贴近且仔细地观照、标记「弯曲、弯曲」,以便了知弯曲时,弯曲动作里逐渐移动的现象。禅修者在此也将能亲身体验到手臂向上移动时的轻盈感觉。

同样的,当想要将弯曲后的手臂再伸直之时,「想要伸直」的动机会先变得显著。就此,你必须观照、标记这个动机:「想伸直、想伸直」。实际将手臂伸直时,你必须观照、标记「伸直、伸直」。如此,手臂伸开移动的现象,在缅语中我们称为「伸直」。当你观照、标记「伸直、伸直」时,你将亲身经验手臂下移时的沉重感觉。

这轻盈感与沉重感的特质,皆被称为「自相」(sabhāva-lakkhaṇa,个别身、心现象所独有的特质)。

箴言:「见自相已,方见生灭。」

如此持续地观照、标记,禅修者将体验到移动时的轻盈与沉重感生起后又灭去。如此对生、灭的了知,即是在了知「有为相」(「依缘而起」或「合会而成」的性质)。[27]

之后,当禅修者证得「坏灭智」,观见坏灭或说灭去的现象时,他了悟到:弯曲的动作不是恒常的,观照弯曲动作的能观之心也不是恒常的;伸直的动作不是恒常的,观照伸直动作的能观之心也不是恒常的。

如此,就在弯曲、伸直手臂的时候,禅修者能对三共相「无常」、「苦」及「无我」,有明晰、彻底且具决定性的了知,并循此而证得一直以来所希求的圣法。

愿你们听闻了今日包含三部分的「毗婆舍那实修教学」之后,能够如所听闻到的那样,精勤修习、实践,并愿你们能够安乐地、快速地证得向来所希求的「圣法」以及「涅盘」(一切苦的止息)。

〔此时〕禅修者说:愿我们具足长老的祝福。

善哉!善哉!善哉! [28]

应谨记的座右铭

☼ 于概念法所缘,观其常恒不变,这是奢摩他的修行。

☼ 于真实法所缘,观其无常,这是毗婆舍那的修行。

☼ 只有在身、心现象生起的当下,观照它们,方能了知它们的「自相」。

☼ 了知「自相」后,才能见到生、灭。

☼ 必须清楚地观察到,生起的一切身、心现象,必然会坏灭、消逝。

☼ 了知坏灭时,将清楚地见到无常。

☼ 见到无常时,苦变得明显。

☼ 苦变明显时,便见无我。

☼ 见无我时,将能证得涅盘。

回向

普为翻译、编辑、出资、出版、印制、

读诵受持、辗转流通、随喜赞叹此书者回向:

愿以此法施功德,回向给父母、师长、亲戚、朋友,

及法界一切众生。

愿他们没有身体的痛苦、没有心理的痛苦。

愿他们福德智慧增长,早日证得道智、果智与究竟涅盘。

善哉!善哉!善哉!

PRACTICAL / WORKING INSTRUCTIONS ON VIPASSANĀ MEDITATION

By

The Most Ven.

Saddhammaraṃsi Sayādaw

Translated by

Daw Khemānandi

BUDDHA SĀSANA YEIKTHA

INTRODUCTION

Of all those who practice Vipassanā meditation, those who have not experienced the dhamma would like to experience the dhamma very quickly. Those who have experienced the dhamma would like to make further progress in the dhamma quickly. They would like to realise the Noble dhamma quickly. Thus, for those who would like to experience the dhamma quickly, to make progress in the dhamma quickly and to realise the Noble Dhamma quickly, you must first listen to the Practical Instructions in such a way that you will be able to recall them thoroughly when you do your practice. You will have to read and study them. Then only you will reach your goals of realizing the dhamma.

One cannot practice Vipassanā meditation by making physical effort. One cannot do it by making verbal recitations. It has to do with the mental faculty or mind.

Thus, it is absolutely crucial that one knows how to:

- keep the mind directly on the object of meditation with pin-pointed precision

- train the mind so that it does not wander to outside objects

- train the mind not to wander for long as and if it does wander out by proper observing and noting.

To be able to do this, one must read, study, memorize and listen to the Practical Instructions in detail. Thus, I would like to advise all those who would like to practice Vipassanā meditation effectively to specially read and study the Practical Instructions.

Saddhammaraṃsi Sayādaw.

PRACTICAL / WORKING INSTRUCTIONS ON VIPASSANĀ MEDITATION

he following is an introductory discourse on the practice of Vipassanā meditation by the Most Ven. Sayādaw of Saddhammaraṃsi Yeiktha (Meditation Centre), given to those yogis who have come to practice Vipassanā meditation at Saddhammaraṃsi Yeiktha Meditation Centre).

Of those who practice Vipassanā meditation, those who have not experienced any dhamma would like to experience the dhamma as quickly as possible. Those who have already experienced some dhamma would like to make quick progress and realise the Noble dhamma quickly. Thus to be able to experience the dhamma quickly, to be able to make progress in the dhamma quickly and to be able to realise the Noble dhamma quickly, you must listen with utmost attention and respect to the following discourse on the practice of Vipassanā Meditation.

In brief, there are three aspects to the “working or practical instructions” on the observing and noting in Vipassanā Meditation.” They are:

- Observing and noting while in the siting posture.

- Observing and noting while in the walking posture.

- Observing and noting on the general details.

Observing and Noting While in the Sitting Posture

I will first explain about observing and noting while in the Sitting Posture. When you are about to do your meditation practice, first you must find a quiet and peaceful place. Then choose the most comfortable posture which will enable you to sit for quite some time. You may sit with your knees bent [7] under you or sit across-legged. After being settled in your posture, keep your back and head erect but not stiff. Then close your eyes and focus your attention on your abdomen.

When you inhale or breathe in, the abdomen Rises or Expands in stages. You must observe this rising with close and intense attention so that your mind is pinpointed on it from the start of the rising to the end of the rising in its entirety, without letting your mind wander out anywhere and note as: “Rising”.

When you exhale or breathe out, the abdomen Contracts or Falls gradually in stages. You must also observe this with close and intense attention, from the beginning of the falling in stages to the end of the falling with pinpointed precision so that your mind does not wander out anywhere and note as “Falling”.

When observing and noting the rising and falling of the abdomen you should dissociate yourself from the physical shape and from of the abdomen as much as possible. As you inhale the air, there arise some tension and pushing in the inside of the abdomen. You must observe and note closely and intensely so as to be able to feel or know this intension and pushing taking place in the inside, as much as possible. The physical shape and form of the abdomen is Paññatti or Concept. Vipassanā is not for Paññatti (Concepts). It is for Paramattha (truth or true nature). The nature of the pushing, tension, pressure etc. taking place inside is Paramattha. This you must observe and note closely and precisely so as to know it.

You must observe and note as carefully when you breathe out. You must dissociate yourself from the form and shape of the abdomen as much as possible. You must observe and note intensely and precisely to know the nature of the gradual and slow movement, vibration and that of receding, as much as possible.[8]

If you feel that you cannot keep your mind clam by observing and noting with these two objects as “Rising, Falling”, you may add another object and observe and note “Rising, Falling, Touching”.

When observing and noting “touching”, you should dissociate yourself from the physical shape and form as much as possible. You must observe and note closely and intensely on the nature of the hardness and tension from the touching.

If you still cannot concentrate enough and your mind tends to wander with these three objects, then you can add another and observe and note with four objects as “Rising, Falling, Sitting, Touching.”

When you observe and note “sitting”, you must observe and note by encompassing from the upper part of your body down and observe and note closely and intensely so as to feel the nature of the stiffness and tension in the body as much as possible. You must dissociate from the shape and form of the head, body, hands and legs as much as possible. You must observe the nature of the tension and pressure produced by the support of the air which has been set in motion by the desire of the intentional mind to sit and note as “sitting”.

When you observe and note with four objects as “Rising, Falling, Sitting, Touching”, your mind will usually become calm. If you find observing and noting as “Rising, Falling, Sitting, Touching” with the four objects is helpful, you may continue with such noting. However, if you find that observing and noting with four objects as such puts your mind in so much strain and worry that you cannot concentrate well, you may want to observe and note with just three objects as: “Rising, Falling, Touching”. If you still find that noting even with three objects, is not helping you because of the worry and strain, you may observe and note with just [9] two objects as “Rising and Falling.” The main objective is to calm the mind and develop concentration.

As a beginner, while noting “Rising, Falling, Sitting, Touching”, your mind may wander out here and there – to the monastery or temples, to the shopping centres, to the house, etc. When your mind wanders out in this way, you must also make your observing and noting mind observe and note this wandering mind as “wandering, thinking, planning etc.”

As your Samādhi (concentration) and Ñāṇa (Insight) becomes relatively strong, you will find that your wandering thoughts disappear as you observe and note “wandering, thinking, planning, etc.” As you continue observing and noting continuously as such, you will come to experience for yourself that the wandering thoughts disappear and pass away after about four or five such observing and noting.

Later, as you progress further in your Samādhi (concentration) and Ñāṇa (Insight) and reach the Insight knowledge known as “The Knowledge of Dissolution (Bhaṅga-ñāṇa)”, as you observe and note “wandering, thinking, planning”, you will find the thinking, planning disappearing with each observing and noting, you will find them passing away with each observing and noting by yourself.

When your Samādhi (concentration) and Ñāṇa (Insight) get really strong, when you observe and note “thinking, planning”, you will come to see not only the thoughts disappearing but the observing and noting mind that observes and notes it also disappearing. Thus you will come to realise that the thoughts, thinking, planning etc. are not everlasting. So also the observing and noting mind is not everlasting. They are Anicca.

One also comes to realise that such swift and rapid [10] succession of arising and passing away is like torture. This is suffering or Dukkha. How can one ward off the nature of these torture-like sufferings, the nature of this suffering of arising and passing away? These sufferings cannot be warded off in any way. This suffering of passing away and torture is having its own course. It is Uncontrollable. They are Anatta. Thus one comes to the realisation or Insight (Ñāṇa) into the truth about Anicca (Impermanence), Dukkha (Suffering) and being Uncontrollable —Anatta.

For the beginner yogi, as you go on observing and noting “Rising, Falling, Sitting, Touching” for about half an hour or 45 minutes, you will notice that your limbs start to ache, tingle or become painful, etc. When such occurs you have to change your observing and noting to such suffering aches and pain, Dukkha Vedanā.

There are three ways to observe and note such suffering from pain or Dukkha Vedanā:

- The first is to observe and note on the pain with the objective of making the pain disappear.

- The second is to make a determination with an aggressive mind to fight the pain so as to get rid of it within this one sitting or within this one day.

- The third is to observe and note so as to know the true nature of the pain.

(1) Observing and noting with the objective of wanting to be relieved of the pain as in the first way means that one is actually craving for the pleasure of having no pain. That means one is having greed (Lobha) for pleasure. The practice of meditation is to rid oneself of greed. Instead one’s observing and noting is now sandwiched with greed (Lobha). Because of this, it will take long for one to experience the dhamma, take long to make progress. That is [11] why one should not observe and note in this way.

(2) The second way where you determine yourself to get rid of the pain in one sitting or one day with an aggressive mind is that the aggressive mind means there is the mental factor of anger (Dosa) and grief (Domanassa) involved. In other words, the determination is tainted with anger and grief. This means the observation and noting is sandwiched with anger and grief. Thus one will take long to experience the dhamma and take long to make progress. That is why one should not adopt this method also.

(3) The third way is to observe and note the pain so that you will come to know the true nature of the pain. This is the way to observe and note. Only when one comes to know the true nature, will Udaya, the arising, and Vaya ,passing away, be seen.

To be able to observe and note so that one will come to know the nature: when pain occurs, yogis usually tend to become tense both in body and mind in accordance with the intensity of the pain. One should try not to tense up in this way. One should try to relax both in body and mind. Yogis also tend to worry about “whether one will have to endure the pain the whole time or during this whole hour”. You must be careful not to have such worries.

You should keep yourself calm and adopt the attitude that “Pain will come and go at its own will and my duty is to keep observing and noting the pain”. You must also adopt the attitude that you will practice “patience” with the pain. To practice patience is the most crucial element in dealing with pain. The saying (in Myanmar) that “Patience leads to Nibbāna” is the most useful maxim in mindfulness meditation.

After making a determination that you will be patient, keep your mind calm and relaxed. You must be careful not to get [12] tensed up in both body and mind. Keep both your mind and body relatively relaxed. Then you must pinpoint your mind direct on the pain.

After that you must try to observe intensely and closely to know the extent and intensity of the pain – how painful is it? Where is the pain most crucial – just on the flesh or skin, or muscles or right down in the bones or bone-marrow? Only after so observing intensely and closely that you should note as “pain, tingling, etc.” according to each type of pain.

The second and successive observation and noting must also be made intensely and precisely in the same way, observing on the extent and intensity of the pain and noting accordingly each successive pain. The observation and noting of the pain should be precise and penetrative and not superficial and note as “pain, pain, tingling, tingling, etc.” in a fast and rote manner. Your observing and noting must be intense and precise. As you keep observing and noting precisely and intensely in this way, you will come to experience very clearly that after four or five observing and noting, these pains and aches become more and more severe.

After reaching a peak, the pain will tend to lessen and recede following its own course. When this occurs, you should not relax your observation and noting. Instead you should continue observing and noting earnestly and enthusiastically on each type of pain. You will then experience for yourself that after every four or five observing and noting, each type of pain becomes less and less. One type of pain will become less and less, then another type of pain becomes less and less and the pain also shifting to another location.

When the yogi sees the changing nature of pain as such, the yogi becomes more interested in the observing and noting in the practice. Continuing in this way, as the Samādhi (concentration) and Ñāṇa (Insight) gets sharper and stronger, you will experience the pain increasing with each observing [13] and noting.

After reaching a peak, the pain usually recedes in its own course. One must not relax the intensity of one’s observing and noting when the pain starts to subside. Instead, one must continue with the same intensity of effort and precise aim. Then one will become to experience by oneself, the pain receding with each observing and noting and the pain changing locations and arising at another location. Thus one will come to realise that pain is not everlasting, it is always changing. It increases as well as decreases. In this way one comes to know more about the real nature of pain.

Continuing observing and noting in this way, when the Samādhi (concentration) and Ñāṇa (Insight) become strong and reach the level of Insight known as “Bhaṅga-ñāṇa – The Knowledge of Dissolution” one will experience, as if seeing clearly by one’s own naked eyes, that pain passes away completely with each observing and noting, as if being suddenly plucked away.

Thus when the yogi sees the passing away with each observing and noting, the yogi comes to realise that pain is not permanent. One’s observing and noting mind has now overwhelmed the pain.

With further deepening of Samādhi (concentration) and Ñāṇa (Insight), those whose Insight Knowledge of “Bhaṅga-ñāṇa – Knowledge of Dissolution” are sharp, are able to experience with each observing and noting, not only the pain but also the observing and noting mind passing away with it.

In the case of those whose Insight knowledge are exceptionally sharp, they will see distinctly three phases passing away. That is, as one observes and notes “pain”, the pain passes away, the consciousness that cognises the pain passes away and also the observing and noting mind passes [14] away. One comes to experience all of them by oneself.

Thus one comes to realise in one’s consciousness (mind) and Ñāṇa (Insight) by one’s own accord, that pain is not everlasting or permanent, neither does the consciousness or feeling of the pain nor the observing and noting mind. That it is Anicca.

The quick succession of passing away or dissolution is like torture, suffering – Dukkha. These torture and passing away cannot be controlled or warded off. It is taking its own course. It is Anatta, Uncontrollable. Thus one realises these truths in one’s conscious mind and Ñāṇa (Insight) by one’s own accord.

When one comes to realise in one’s conscious mind that pain is Anicca – Impermanent, Pain is Dukkha – Suffering, Pain is Anattta – Uncontrollable and when one’s Insight into Anicca, Dukkha and Anatta are explicit, thorough and conclusive, one will be able to realise the Noble dhamma that one has been wishing and aspiring for. My explanation on the observation and noting of Vedanā (painful feelings) is fairly complete.

Observing and Noting on Hearing

While doing your practice, you may hear sounds from the outside. You may also see or smell things. You may especially hear sounds – like the sounds of cocks, birds, hammering & beating sounds, people, cars, etc. When you hear such sounds, you must observe and note as: “hearing, hearing”. You must try so as to be able to pay only “bare” attention to the sounds. That is, you must try not to let your mind follow these sounds or let yourself be carried away by imagining about them. You must take care to let it be just “bare” hearing and observe and note as “hearing, hearing”.[15]

When your Samādhi (concentration) and Ñāṇa (Insight) get relatively strong, as you observe and note “hearing, hearing”, the sounds may become unintelligible, as if from far away, or as if being carried far away, or getting nearer or become hoarse and not clear. If you experience such, that means you will now be able to observe and note on your hearing consciousness.

As you go on observing and noting in this way and your concentration and Insight get stronger, you will experience that as you observe and note “hearing, hearing” the sounds disappear syllable by syllable, the sounds pass away syllable by syllable, the hearing consciousness (that hears the sound) passes away, one by one, and the observing and noting mind that observes and notes the sound also passes away. Yogis whose insight knowledge are sharp are able to experience them very clearly and distinctly.

What is specially evident is that, even those yogis who are beginners in observing and noting sounds are able to experience distinctly the sounds disappearing syllable by syllable. The sounds are not connected to each other anymore. They disappear syllable by syllable. For example, when one hears the sound of the word “Gentleman” and observe and note as “hearing, hearing”, you will experience the sound of the syllable “Gen” pass away separately, the sound “tle” passing away separately and the sound “man” passing away separately. Thus they are heard in such broken sequence that the meaning of the word becomes obscure and unintelligible. Only the passing away of the sounds in broken sequence becomes evident.

When you experience the sounds passing away, you will come to realise that the sound is not permanent. When you experience the observing and noting mind also passing away, you will realise that the observing and noting mind is also not permanent. Thus you will realise that the sound that is heard is not permanent nor is the observing and noting [16] mind permanent. That is Anicca. The quick succession of such passing away is like torture – suffering (Dukkha).

How can one ward off these torture and suffering? One cannot stop or ward this off. This torture of passing away is taking its own course, it is Uncontrollable or Anatta. Thus while observing and noting “hearing, hearing” one will be able to realise the Insight knowledge (Ñāṇa) of Anicca, Dukkha and Anatta and realise the Noble Dhamma.

While Obsering and Noting in the Sitting posture

Observing and noting in the sitting posture as “Rising, Falling, Sitting, Touching” has to do with the physical body or Kāya. So, it is known as Kāyānupassanā Satipaṭṭhāna. Observing and noting as “Pain, numbness or aching” has to do with the feelings (feelings of the physical sensations) or Vedanā, so it is known as Vedanāupassanā Satipaṭṭhāna. Observing and noting on the conscious mind as “wandering, planning, thinking, etc.” has to do with the mind or acts of consciousness— Citta, so it is known as Cittānupassanā Satipaṭṭhāna. Observing and noting as “seeing, hearing, smelling, etc.” has to do with the nature of physical or mental objects known as dhamma. So, it is known as Dhammānupassnā Satipaṭṭhāna.

Thus while practicing in one sitting posture as instructed by our benefactor, the Ven Mahāsi Sayādaw, there is included all the four practices of Satipaṭṭāna. My explanation on the sitting posture is fairly complete.

Observing and Noting While in the Walking Posture

Now I will explain to you how to observe and note while in the walking posture. There are four ways of observing or noting in the walking posture. They are:[17]

- Observing and making one noting with one step.

- Observing and making two noting with one step.

- Observing and making three noting with one step.

- Observing and making six noting with one step.

Observing and Making One Noting with One Step

In this way, one has to observe and make note of the step as one movement as: “Left step, Right step”.

When you observe and note “Left step” you must observe and note intensely and closely so that you will come to know the nature of the forward movement in stages, from the beginning of the step to the end of the step. You must try to dissociate from the physical form and shape of the foot as much as possible. Similarly with the “Right step”. You must observe and note intensely and closely so that you will come to know the nature of the forward movement in stages, from the beginning of the step to the end of the step. You must try to dissociate from the physical form and shape of the foot as much as possible. My explanation on making one noting with one step as “left step, right step” is fairly complete.

Observing and Making Two Noting with One Step

In this 2nd way, you observe and make note of the step as two movements as: “Lifting, Dropping, Lifting, Dropping”. You must focus on the nature of the gradual upward movement, movement by movement, as much as possible as you observe and note “lifting”. Again you must dissociate from the physical form and shape of the foot as much as possible. Similarly, when you note “Dropping” you must dissociate from the physical form and shape of the foot as much as possible and observe keenly and intensely to know the nature of the gradual downward movement, movement by movement. [18]

The physical form and shape of the foot is Paññatti — concept. Concepts are not objects of Vipassanā. The nature of motion or movement is Paramattha — truth or true nature. It is Vāyo Paramattha. My explanation on making two nothing with one step is fairly complete.

Observing and Making Three Nothing with One Step

This 3rd way is to observe and note as three movements in one step as: “Lifting, Pushing Forward, Dropping”. When you observe and note “lifting,” you must observe and note closely and intensely to know the nature of the gradual upward movement in stages as much as possible as explained above. When you observe and note as “Pushing Forward”, you must observe and note closely and intensely to know the nature of the gradual forward movement in stages as much as possible. When you observe and note “Dropping,” you must observe and note closely and intensely to know the nature of the gradual downward movement in stages, as much as possible.

When so observing and noting closely and keenly all these movements, you must observe and note in such a way that you are right with the “present movement” of the momentum (duration) of the movement (Santati Paccuppanna). You must also observe and note closely and intensely to know the nature of the movement, Paramaitha. When you are able to observe and note “Lifting”, you will come to experience by yourself not only the gradual upward movement, movement by movement, but also that it becomes lighter and lighter as it moves upward.

As you observe and note “Pushing Forward” also in this way, you will come to experience not only the gradual forward movement, movement by movement, but also that it becomes light as it moves forward. When you observe [19] and note “dropping” also in this way, you will not only experience the gradual downward movement, movement by movement, but also that it becomes heavier and heavier as it goes down.

When a yogi experiences the sensation of lightness in the gradual upward movement as he/she observes and notes “lifting”, the sensation of lightness in the gradual forward movement as he/she observes and notes “pushing forward”, the sensation of heaviness in the gradual downward movement as he/she observes and notes “dropping,” the yogi becomes especially interested in his/her practices. It means experiencing the beginning of the dhamma for the yogi.

Experiencing lightness in the different movements means experiencing the characteristics of Tejo Dhātu — element of heat & cold and Vāyo Dhātu — element of motion or movement. Experiencing heaviness in the downward movement means experiencing the characteristics of Paṭhavī Dhātu — element of extension, toughness or hardness, and Āpo Dhātu — element of cohesion and fluidity. Experiencing such means experiencing the beginning of the Noble dhamma. My explanation of three noting with one step is also fairly complete.

Observing and Making Six Noting with One Step

The 4th way is to make note as six movements in one step as: “Beginning to Lift, End of Lifting; Beginning to Push Forward, End of Pushing Forward; Beginning to drop, End of Dropping”. “Beginning to lift” means only the heel has been raised. “End of lifting” means the whole foot together with the toes has been raised. “Beginning to push forward” means the foot has just “started” to push forward. “End of pushing forward” means the stage of the foot that is in short pause before descending. “Beginning to drop” means the beginning stage of descending or dropping. “End of dropping” means when the foot touches the ground or floor. Actually this is just dividing the three movements in one [20] step into six as: beginning and ending”.

Another way is to observe and note as: “Wanting to lift, Lifting; Wanting to push forward, pushing forward; Wanting to drop, dropping”. In this type of observing and noting, the mental phenomena, Nāma (Wanting to…) and physical phenomena, Rūpa (lifting, etc.) are observed and noted separately.

Still another way is to observe and note as: “Lifting, Raising; Pushing Forward; Dropping, Touching, Pressing”. When you observe and note “Lifting” it is the stage where only the heel starts to lift. “Raising” means the whole foot together with the toes is raised. “Pushing Forward” means pushing the foot forward as just one movement. “Dropping” means starting to put the foot down. “Touching” means when the foot touches the ground or floor. “Pressing” means pressing the foot in order to lift the other foot. Thus you will note as: Lifting, Raising, Pushing Forward, Dropping, Touching, Pressing” in six movements. Many yogis are able to develop their Samādhi (Concentration) and Ñāṇa (Insight) by noting with such six movements and make progress in their observing and noting. They are able to realize the dhamma in a very distinctive way. My explanation of observing and noting on the walking posture is fairly complete.

Observing and Noting on the General Details

Observing and noting on the general details means it is not the time for the sitting posture. It is also not the time for the walking posture. They are the little details that you do when you return to your living quarters such as: opening door, closing the door, making the bed, changing clothes, washing clothes, preparing meals, eating, drinking, etc. and observing and noting them. [21]

§3.1 Observing and Noting while Having Meal

The moment you see the meal, you observe and note “seeing, seeing”. When you stretch your hand to reach the food, observe and note “stretching, stretching”. When you touch the food, observe and note “touching, touching“. When you collect and arrange your food, observe and note “arranging, arranging”. When you bring it to your mouth, observe and note “bringing, bringing”. When you bend your head to take the food, observe and note “bending, bending”. When you open your mouth, observe and note “opening, opening.” When you put the food in your mouth observe and note “putting, putting”. When you raise your head again, observe and note “raising, raising”. When you chew, observe and note “chewing, chewing”. When you are aware of the taste observe and note “knowing, knowing”. When you swallow, observe and note “swallowing, swallowing”.

These instructions are in accordance with the way our benefactor, the Ven. Mahāsi Sayādaw, observes and notes while taking a morsel of food. They are meant for those yogis who take their practice seriously and also practice incessantly, without a gap, and respectfully and intensely.

At the beginning of the practice you will not be able to observe and note all the movements. You will forget to note most of the movements, but you must not be discouraged. Later when your concentration and Insight become mature, you will be able to observe and note all the movements.

At the beginning of the practice, you must first try to focus on the most distinctive movement for you as your main object. What is the most distinctive movement for you? If stretching you hand is the most distinctive movement, then you must try to observe and note “stretching, stretching” without missing or forgetting. If bending your head is most distinct, try to observe and note “bending, bending” without [22] missing or forgetting. If chewing is most distinct try to observe and note “chewing, chewing” without missing or forgetting. You should thus try to observe and note at least one distinctive movement as you main object without missing or forgetting.

Once you can focus your mind on one object closely and precisely in this way and develop concentration, you will be able to focus and observe and note other movements and develop further Samādhi (concentration) and Ñāṇa (Insight). Various levels of Vipassanā Insight will consequently unfold and one can realize the Noble Dhamma while taking your meal.

The chewing movement is especially more distinctive. Our benefactor, the Ven. Mahāsi Sayādaw, has once said that of the two jaws, it is the lower jaw that is involved in the chewing movement. This movement of the lower jaw is actually what we call “chewing” in our Burmese vocabulary.

If you can observe and note this gradual movement of the jaw well and develop concentration, you will find the observing and noting on the chewing movement to be especially good. Beginning with this chewing movement you will also be able to observe and note all the movements involved in taking a meal. My explanation on how to note the general details in taking a meal is fairly complete.

Observing and Noting on the Motion of Sitting Down

Observing and noting on such behaviors as “sitting standing, bending, stretching” are also part of observing and noting the general details. For those who have reasonable foundations of Samādhi (concentration) and Ñāṇa (Insight), if one is especially aware, the “desire of intention to sit” when one is about to sit down will be quite evident. Thus one must observe and note this intention or desire as [23] “wanting to sit, wanting to sit”. Then when the actual movement of sitting occurs, one must observe and note “sitting, sitting.”

When you observe and note “sitting” try to dissociate from the form of head, body, legs, etc. as much as possible. You must observe and note closely and intensely on the nature of the gradual downward movement, movement by movement, as much as possible. You must also observe and note in such a way that your mind stays pinpointed on the momentum of the “present moment” of the downward movement, moment by moment.

You must also observe and note very closely and precisely to be able to know the true nature (Paramattha) of the movement. After you are able to observe and note closely and intensely and are able to pinpoint your observing and noting mind on the “momentum of the present moment” of the movement, as you observe and note “sitting, sitting” you will realise by yourself clearly that you not only come to know the gradual downward movement but are also able to feel the sensation of getting heavier and heavier as it moves downwards.

Observing and Noting on the Motion of Standing up Again.

When you are about to get up or stand up after sitting, if you are especially mindful, the “desire or intention to get up” will first become evident. You must observe and note this intention as “wanting to get up, wanting to get up”. This desire to get up sets in motion Vāyo Dhātu — the element of motion, which pushes you up. As you bend forward to collect your energy to get up, you must observe and note as “collecting energy, collecting energy”. When you stretch your hand to the side for support observe and note “supporting, supporting”.

When the body becomes filled with energy, it will gradually [24] rise upwards in stages. This upward movement, we call standing up/ getting up in our Burmese vocabulary. We observe and note this as “standing up, standing up”. A vocabulary is also Paññatti (Concept). What we must know is the nature of the gradual upward movement, movement by movement, as much as possible. We must also observe and note intensely and precisely so as to be with the momentum of the “present moment” of the movement of the gradual upward movement.

When you are thus able to observe and note closely, intensely and precisely to be with the momentum of the present moment and to also know the nature of the Paramattha, when you observe and note as “standing standing”, as the body reaches higher up, in addition to knowing the gradual upward movement in stages, you will come to experience by yourself, the sensation of lightness as it rises upward.

In this way, you will come to experience by yourself the sensation of heaviness with the gradual movement downwards as you observe and note “sitting” and the sensation of lightness with the gradual movement upwards as you observe and note “getting up”. Experiencing the sensation of lightness in the upward movement means seeing the nature of “Tejo Dhātu and Vāyo Dhātu”. Experiencing the sensation of heaviness in the downward movement means seeing the nature of “Paṭhavī Dhātu and Āpo Dhātu.”

Seeing the Arising and Passing Away.

Motto: Only when the nature is known, Udaya-vaya will be seen.

After coming to know the nature of the particular phenomena, one will come to know Udaya — the arising and Vaya — the passing away. That is, one will come to see [25] the arising and passing away of each movement, from moment to moment. There is the arising of one movement and its passing away, then another arising of the movement and its passing away, and on and on. Seeing clearly the arising and passing away is Saṅkhata-lakkhaṇa (compound or conditioned characteristics of all mental and physical phenomena).

Continuing observing and noting after seeing the arising and passing away in this way, when one’s concentration and insight become strong, you will find the arising not so distinct anymore. Only the dissolution or passing away is distinct. Experiencing the passing away more distinctly, one comes to realize that no bodily behavior is permanent. Then when one sees clearly the noting mind also passing away, one will come to realise that the noting mind is also not permanent. Both the mental (Nāma) dhamma and physical (Rūpa) dhamma are impermanent, that they are Anicca.

The swift and rapid succession of passing away is like torture. Suffering — Dukkha; that such passing away or dissolution and torture cannot be stopped or warded off, that it is taking place at its own will. Uncontrollable — Anatta. When one’s insight knowledge of this Anicca, Dukkha and Anatta becomes very explicit, thorough and conclusive, one will be able to realise the Noble Dhamma that one has been wishing and aspiring for.

Thus while observing and noting “sitting” and “standing up”, one will come to realise the general or common characteristics of Anicca, Dukkha and Anatta called Sāmañña-lakkhaṇa. When one is clear, explicit, thorough and conclusive about this Sāmañña-lakkhaṇa, one will be able to realize the Noble Dhamma that one has been wishing and aspiring for. [26]

Observing and Noting on Bending and Stretching

Observing and noting on bending and stretching are also part of observing and noting the general details. When you have to bend your arm, if you are especially mindful, the “desire” to bend will first become prominent. Thus you must observe and notes as “wanting to bend, wanting to bend”. After that, you must observe and note closely and attentively to know the nature of the gradual movement of the bending behavior as it bends as much as possible. Here also one will be able to experience the sensation of lightness as it moves upward by oneself. Here also one will be able to experience the sensation of lightness with the upward movement.

When one wants to stretch the arm back after taking care of whatever need to be taken care of by bending, the “desire” to stretch will also become evident first. You must observe and note this desire as “wanting to stretch, wanting to stretch”. When the actual behavior of the stretching occurs, observe and note as “stretching, stretching”. This nature of the outward and downward movement of the arm, we call “stretching” in our Burmese vocabulary. As you observe and note “stretching, stretching”, you will also experience the sensation of heaviness as it falls downward by yourself.

The characteristics of lightness and heaviness are called Sabhāva-lakkhaṇa (specific or particular mark or characteristics of mental and physical phenomena).

Motto: Only when the nature is known, Udaya-vaya will be seen.

Continuing observing and noting in this way, one will come to experience that the lightness and heaviness in the nature of the movement arise and pass away. This knowing of arising and passing away is knowing Saṅkhata-lakkhaṇa (compound or conditioned characteristics). [27]

Later, as one reaches the level of Insight of Bhaṅga- ñāṇa — Knowledge of Dissolution — and sees the dissolution or passing away, one comes to realise that: the behaviour of bending is not everlasting and the noting mind on the bending behaviour is also not everlasting; the behaviour of stretching is also not everlasting, nor the noting mind on the stretching behavior everlasting by yourself.

Thus while bending and stretching, one can have a clear, explicit, thorough and conclusive knowledge of the characteristics of Anicca, Dukkha and Anatta and realize the Noble Dhamma that one has been wishing and aspiring for.

Thus having listened today to the three aspects on the Practical Instructions on Vipassanā Meditation, may you be able to follow, practice and develop accordingly and may you be able to realize the Noble Dhamma that you have been wishing and aspiring for, and realize the peace of Nibbāna — the extinction of all suffering — swiftly, with ease of practice.

Yogis: May we be fulfilled with the Ven. Sayādaw’s blessings. Sadhu! Sadhu! Sadhu! [28]

Maxims For Recollection

☼ Observing and noting on the object of Paññatti as permanent is Samatha.

☼ Observing and noting on the object of Paramattha as impermanent is Vipassanā.

☼ Only when observing and noting is made at the very present moment of arising, will Sabhāva be really known.

☼ Only when the nature is known, will Udaya-vaya be seen.

☼ All arising physical and mental phenomena must be explicitly observed and noted as ending inevitably in passing away or dissolution.

☼ When the passing away or dissolution is known, Anicca will be explicitly known.

☼ When Anicca is seen, Dukkha becomes evident.

☼ When Dukkha is evident, Anatta is seen.

☼ Seeing Anatta, Nibbāna will be realized.

Short Biography

Ven. Saddhammaraṃsi Sayādaw, Sayādaw U Kundalā bhivamsa, a senior disciple of the late Most Ven. Mahāsi Sayādaw, is the founder and Chief Abbot of Saddhammaraṃsi Medi-tation Centre in Myan- mar. He is also a Mahāsi Nāyaka (one of chief advisory Sayādaws of the main Mahāsi Centre in Myanmar).

The Ven. Sayādaw entered the monastery at the age of nine & studied at various well known monasteries in Myanmar. The Ven. Sayādaw holds three Dhamma Lectureships & taught at the well known Maydini Forest Monastery for twenty years. After training under the late Most Ven. Mahāsi Sayādaw, the Ven. Sayādaw founded the Saddhammaraṃsi Meditation Centre in 1979, with the blessing of the late Most Ven. Mahāsi Sayādaw. The Centre has about 200 yogis daily. Sayādaw has since established 2 branches in the country side & one in the suburbs. Sayādaw has published many dhamma books and has traveled throughout Europe, U.K., U.S., Canada, Australia, Japan & the East. The Ven. Sayādaw holds the title of Agga Mahā Kammaṭṭhanācariya awarded by the government of Myanmar.